Emma Baccellieri

John Hankins had a request for MLB playoff teams this October:

Please be willing to cut holes in your hats.

Hankins is one of the inventors and founders of PitchCom—the device that clubs started using this year so catchers can transmit calls to pitchers instead of visually giving signs. The set-up is fairly straightforward. The catcher presses buttons on his wristband to communicate pitch type and location, which the pitcher will hear through a receiver tucked into his hat, and the same goes for any relevant fielders. (The shortstop and second baseman will typically also be wearing receivers.) While not every team started out the year with PitchCom, more hopped on board as the season wore on, and by September, the device had become so common it was almost unremarkable.

But October presented a new challenge for PitchCom: The playoffs are loud. They’re really loud. In an environment where teams are desperate for every possible competitive advantage, no one wanted to go back to ordinary, visual signs that would be at risk of getting stolen. But if they were sticking with PitchCom in front of tens of thousands of noisy, championship-hungry fans… how were they going to hear?

Hankins and his co-founder, Craig Filicetti, had been thinking about the problem for months. They worked on a series of adjustments over the course of the season: They reconfigured the audio, getting a sound engineer to optimize the pitch calls for loud environments, and designed several versions of a modified receiver with an earpiece that could amplify the sound even more. And they also made one very simple suggestion: Cut a little hole in each ballcap so the receiver wouldn’t be muffled by fabric. But perhaps no one on a baseball diamond can be as particular, or as paranoid, or as prone to suspicion as a pitcher: You want to cut a hole in my hat? There was pushback to the early suggestions.

“We begged teams to cut holes in their hats,” Hankins recalls, clad in a PitchCom t-shirt and hat before taking in an NLCS game at Petco Park. “Just a hole in the hat.”

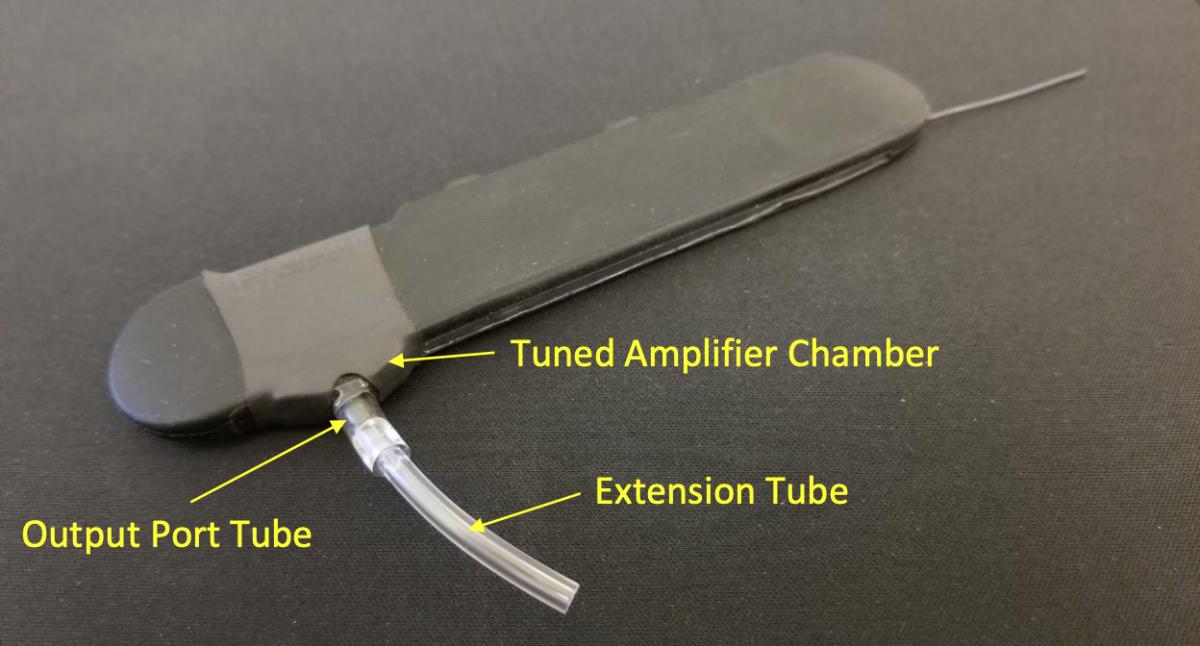

They ended up making some adjustments to the plan before October: They ditched the full earpiece, instead settling on a version with an amplifier chamber and a small tube, which still requires (yes) a little hole in the seam of the ballcap. The players ultimately liked this one much better. By mid-October? Just about everyone was on board.

“[It’s] like a little tube coming down through a little hole in our hat that goes basically right into our ear. We know these playoff environments get really loud,” Phillies starter Zack Wheeler said. “But I’ve been just fine hearing it … Somebody came up with that, I don't know who did, but we started using it.”

It was Hankins and Filicetti. And following lots of tweaking and incorporating feedback, they’re pleased with how it’s been received, even in the noisiest of environments.

“It seems to be working. It really has,” Padres catcher Austin Nola said during the NLCS. “We might have had one little issue, but I think at the end of the day everybody has really liked it. It takes away from having to put signs out and the ability to steal signs from second base. I think it's been a good addition.”

The question of how loud PitchCom should be has always been central to the device. When Hankins and Filicetti tried out a prototype early last year, they had 10 volume settings, and they worried that a “10” might be too loud. Weren’t teams going to be concerned about the batter hearing what pitch was coming?

Nope, the early feedback went. It needed to be louder, not softer, and so they created a new version where the volume scale went up to 20.

Every bit of that has been needed in the playoffs. Phillies shortstop Bryson Stott, for instance, typically set his PitchCom at eight in the regular season: “I don’t like feeling like it’s yelling in my ear,” he said. “So I just keep it low.” But for the first postseason game at Citizens Bank Park in Philadelphia, he found himself going up, and up, and up.

“My PitchCom was at 20,” he said, “and I still had to cover it to hear what pitch was coming.”

In other words, they’ve needed every volume enhancement they could make.

The most basic of these is reconfiguring the audio. PitchCom has worked with a sound engineer in Nashville to go over every single track—adjusting frequency and amplitude to optimize them for a loud stadium. The engineer has been kept busy. Some teams have a habit of tinkering with and adding to their pitch calls. Though PitchCom comes with a standard collection of pre-set tracks (“four-seam fastball,” “curveball,” and so on, available in English, Spanish, Japanese and Korean), a number of clubs decided to record their own. Some are just basic calls done in a different voice. A few are highly specific to a given pitcher or scenario. Others are simply motivational. One reliever had his team program in the voice from the video game Mortal Kombat saying “Finish him.” (Who wants to hear “heater” when you can hear that?) One club has a far more profane version of “Throw it over the plate, you wimp.” And Guardians catcher Austin Hedges has become known for his “f— yeah” button.

“Teams were very creative,” Hankins said, “which is all we wanted.”

There are about 10 clubs who stuck with PitchCom’s pre-programmed tracks. The others decided to make their own this season. All four of the teams that made it to the ALCS and NLCS—the Astros, Yankees, Phillies and Padres—customized their tracks, Hankins said. All have been worked over by the sound engineer to better cut through loud noise.

The next part of the equation was modifying the receiver. Hankins and Filicetti first worked with an audiologist to design an earpiece—trying to strike the right balance of being loud enough for players to hear audio without blocking out any external noise they still needed to hear.

“We wanted to make sure that they had sound awareness,” Hankins says. “Especially pitchers, they hear the ball off the bat, they have to know if it’s a good one or a bad one.”

By August, they thought they had the right formula. They tested the earpiece that month in game situations in High A and provided them to major-league clubs in playoff contention to try out on their own. But the feedback wasn’t great: Players weren’t a fan of having to stick anything in their ears while on the diamond.

“They were very nice about it,” Hankins says. “But no one really loved it.”

Yet the earpiece was just one part of the modified receiver. It was connected to a tuned amplifier chamber with a pair of tubes. It didn’t take long to realize their answer might be removing the earpiece while leaving most of the rest of the design. “We pulled the tube out, and I said, what happens if you just poke a hole in the hat, and let it stick out?” Hankins says. Playoff teams still have the earpieces if they need them—a “break-glass-in-case-of-emergency” deal, as he describes it. But no one has had to use them yet this October.

In short: The enhanced audio tracks are easier to hear. The amplifier chamber makes them even louder. The little hole in the hat means the receiver is not muffled by any fabric, and the tube works as a miniature megaphone of sorts, putting the sound physically closer to the players’ ears without actually being in them. With all of these changes, the system has generally been loud enough for players to hear, even in the loudest of stadiums.

Hankins and Filicetti are pleased overall with how PitchCom has worked this year. In its first season in the majors, it helped the average time of game drop by six minutes, and they’re encouraged by the fact that teams grew more comfortable with it over the course of the season. That’s helped them continue to troubleshoot and work out kinks—which can be as much about growing players’ understanding of PitchCom as it is about changing anything with the device itself.

For instance, the “one little issue” referenced by Padres catcher Nola? When San Diego starter Mike Clevinger had a brief problem against the Dodgers in the NLDS on Oct. 11, it turned out his device itself was actually fine. The tube had slipped and gotten tangled in his sweaty hair. A clubhouse attendant brought out a new receiver for him, but he realized that he simply had to adjust his existing one, and he was able to keep going.

With the playoff volume adjustments, players have actually joked about it being too loud, rather than too quiet.

“PitchCom is pretty neat. They're pretty great … [But] maybe if you've got the volume way up, and you get that silent moment and you're going to get the pitch, and it's going to be so quiet that maybe the batter would hear it,” Cardinals starter Miles Mikolas said before his wild-card start with a laugh. “He hit a game-ending home run, and I heard the PitchCom go fastball inside! That would be a neat one.”

But that hasn’t come to pass just yet: In October, everyone involved has realized, even the quietest moments are still pretty loud.

Share:

PitchCom® Has Done More Than Stop Sign Stealing…It Has Given Pitchers Advantages They Never Had Before

How Two Magicians Solved Baseball's Unsolvable Problem